It was 20 January 2011, just five days before a major protest called for by many youth and opposition groups in Egypt, when Ali came across a hilarious image on Facebook. One of his friends had shared a photoshopped painting depicting Mubarak atop a majestic stallion as if marching into battle. The then president’s face sported the same cheeky imbecilic smile for which he had come to be known and ridiculed privately. Ali recalls laughing out loud at the absurdity of the image, especially since the original painting, which had been edited to include Mubarak, was none other than Jacques-Louis David’s early nineteenth century masterpiece Napoleon Crossing the Alps. Innocuously funny as it was, Ali didn’t share it on his Facebook timeline for fear that it may result in his surveillance or intimidation by the state. In the months and years that followed the toppling of Mubarak, Ali would rarely hesitate to post similar images that lampooned the country’s subsequent heads of state. During the time of the Supreme Council for the Armed Forces, Ali frequently posted anti-military satire and during Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood’s presidency, Ali was unrelenting in his relaying of sarcastic jibes at him and his party. Even in this current period, al-Sisi is the subject of Ali’s frequently-shared sarcastic memes.

* * * *

All too often the Egyptian revolutionary tumult of the past four years has been reductively attributed to the mobilization of youth ahead of 25 January 2011 using social media generally and Facebook specifically. Volumes have been written and many more are in press that portend to disentangle the complexities of the Egyptian new media milieu and explain the sequence of events (online and offline) that precipitated the popular eighteen-day uprising and subsequent public mobilization. Many, myself included, have cautioned against the overzealous, almost fetishistic, fascination with virtual expression and its view as both a litmus test for national revolutionary sentiments and the most pronounced platform for the understanding of public opinion in the country. At this point, it is fair to assume, most such prognostications have been sufficiently problematized and need no further review here.

Nevertheless, with Internet penetration rising steeply since 2011, more and more Egyptians are turning to social media to stay informed and correspond with networks of friends. A large proportion of the information they produce and share falls into the categories of either news/information or entertainment/leisure. However, a growing category of content being generated and distributed is an amalgamation of news and recreation--what could be considered cross-genres. Among the most compelling of these cross-genres are the fragmented bricolages of online memes. This essay is a preliminary intervention into the growing discussion about the content and function of Egyptian revolutionary memes as a form of user-generated content that has registered unparalleled popularity in the country in the years that followed the toppling of former president Hosni Mubarak.

In the fray of political instability and degraded livelihoods at the hands of both the state and socioeconomic conditions, the priorities of scholarship on mediated expression in Egypt may not privilege memes–often dismissed as inconsequential fabrications, frivolous online humor, and interventions with little to no utility. Not only is this view myopic, it dismisses one of the primary avenues and forms of expression for disaffected Egyptian youth online and overlooks an organic transformative dialectic unfolding between the political establishment and society with a growing proportion of the population. It also neglects a sizeable space for alternative discourse construction, a substantial shaper of public opinion, and an arena for disruptive dissident agenda setting that confront mainstream statist propaganda.

Instead, the importance of researching memes lies in the recognition that they serve as an exploratory arena whereby cultural histories meet with extemporaneous reactive production. This is best illustrated in the political arena where Egypt has witnessed an uptick in political awareness and engagement in recent years. Today there are few pieces of reported political news from the mainstream media that are not sifted and interrogated for irregularity, incongruence with familiar lived tropes, or analyzed for hyperbole by communities of online actors and activists. Once the subject matter is deemed worthy of critique and/or ridicule, members of meme communities begin generating memes comprised of doctored versions of original images, audio recordings, or video content. These are then circulated online in hope of acquiring popular traction (virality).

To take stock of this phenomenon, it is necessary to comprehend the scope and reach of these meme–generating communities in/on Egypt. If one were to focus exclusively on those meme communities that generate predominantly political content, a sample of the more successful and popular pages on Facebook include Asa7be Sarcasm Society which has over four and a half million followers (with tens of spinoffs each having hundreds of thousands of followers), Egypt’s Sarcasm Society which has over three and a half million followers. As a comparison, the prominent and premier mainstream satellite station Al-Jazeera Mubashir Misr (Arabic) channel has six million and the largest political party in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood`s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP), has less than two million followers. More recent pages dedicated to the critique of the sitting government include Coup Sarcasm Society which has just under one and a half million followers. Its alternative is the anti-Islamist page called Ana ikhwan, ana m`taf bi wedan (I’m Muslim Brotherhood, I’m a basket with handles) has half a million followers.

Each of these pages is teeming with activity as members actively generate new content in response to the topsy-turvy politics of contemporary Egypt. Members are both the creators and recipients of this content. They are the judges of what works and what doesn’t, what garners popularity and what doesn’t, what becomes part of this collectively curated cultural exhibition and what doesn’t. Each of these pages further contributes to, often reinforcing, the political worldview of a majority of its members. As memes are inscribed with layers of criticism, they represent the instantaneity of responses to mainstream political news coupled with established motifs, symbols, and artifacts from popular culture and contemporary folklore. Often used as tools of contestation, these memes are, from their moment of inception and distribution, instruments in the negotiation of public opinion.

[Image courtesy of Contemporary Art Facebook Page]

Richard Dawkin’s The Selfish Gene is often credited with originating the nomenclature behind the term memes. Dawkins calls memes “the unit of cultural transmission” but suggests that there is little intentionality. Borrowing from genetic vocabulary, Dawkins saw memes as “objective” with near-scientific precision. The term has since become suggestive of an expression that serves a communicative function, that is transferable and modifiable, within which imbued meaning is constructed from layers of semiotic inflection. Coming from evolutionary biology, the term has come to connote hereditary rigidity. Alternatively, other connotations derived from the genetic roots of the term are befitting the way in which memes are used by Egyptian youth. Through mutability and “cross-breeding,” or in the cultural realm, hybridization, creolization, and bricolage, both the transformation and transference of ideas produces novel forms with residual relatability and traceable genealogy.

So while memes often take on a life of their own in their propagation and distribution, they remain, unlike the roots of the term, intentional and engineered interventions by cultural creators and social actors with agency and conviction. Hence, memes, unlike genes, travel throughout the cultural and political corpus not on the basis of pre-determined rules but rather engineered by a constellation of individual and collective will. However, this does not mean the distribution of memes is haphazard or ungoverned by patterns. They are not arbitrary as they are driven by the desire to agitate and often resort to the collective memory of popular culture. So, while memes are far from predictable, they are not arbitrary. While memes are always intentional, they are rarely consequential. It is not necessary to outline general examples of memes, but by way of basic illustration, some prominent political memes from the United States include Mitt Romney’s gaffe “Binders Full of Women,” “Texts from Hillary,” and most recently Obama’s “tan suit.”

Beyond any strict definitions of the term, conceptually, memes are not a function of the digital experience per say but rather far predate modern day communication technology. Nevertheless, the function of this contemporary iteration of collective meaning making, particularly its online form, presents a manifestation that has its own particularities. In the context of the Egyptian digital milieu specifically, it is most important to recognize one of the most instrumental revolutionary memes—the image of slain Alexandrian Khaled Said.

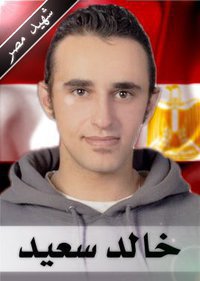

Shortly after the brutal killing of twenty-eight-year-old Khaled Said at the hands of two police officers outside an Internet café, a photograph of the young man’s brutalized and contorted face was taken at the morgue and circulated widely at first via SMS and later online via social media. The shockingly gruesome picture gained traction quickly and precipitated an outpouring of grief and outrage against the police. The admins of the now famous “We Are All Khaled Said” Facebook page—Wael Ghonim and AbdelRahman Mansour—both identify this photo as the open salvo and driving force behind the creation of the page and the revolutionary campaign that ensued. It was then, in the summer of 2010 that Khaled Said went from being an average disaffected young Egyptian to an iconic figure. His photos, both before and after the attack, became abundant online and offline. They were widely used as people’s Facebook profile photo as acts of solidarity and to mourn his loss. As silent stands in his honor and protests proliferated across the country, individuals and groups began modifying Khaled’s image to create posters, banners, caricatures, cartoons, murals, pamphlets, masks etc. in his likeness. Khaled Said had become the meme that agitated the public at large against the police brutality at first and later the state. In the process, he had also become part of Egyptian cultural history and popular culture.

[Widely circulated image of Khaled Said superimposed over

the Egyptian flag with the banner reading Egypt`s martyr]

Omnipresence and Setting the Agenda

Often what increases the virality of a digital utterance is either its ability to tap into the collective memory, arouse a sense of consciousness, or speak to an iconic relatable moment. On 11 February 2011, the most opportune moment for collective national memorialization and iconization unfolded in a thirty-second video from then vice-president Omar Suleiman announcing that Mubarak was stepping down from the presidency. Eighteen days of protests and societal anguish all culminated in and informed that short video. In a moment of national euphoria, the witty online circles had noticed the peculiar placement of a frowning man directly behind the stoic and stone-faced Omar Suleiman. Unable to identify this person who appeared to trespass on the video in hilarious “photobomb” style, he simply became known as “the man behind Omar Suleiman.” Within a matter of hours, hundred and later thousands of photoshopped images showed the man posing behind various landscapes and historical periods.

[Omar Suleiman gives speech as man peers from behind. Screenshot from Egyptian Satellite Channel]

Unlike previous Egyptian memes, the “man behind Omar Suleiman” grew out of a powerful moment of virality and resonated as a result of widespread communal identification. It also had become the first exclusively digital meme from Egypt and the first successful meme to respond directly to news. This characteristic of negotiating with and in most cases negating mainstream politics and political expression in real time has become the substance of Egypt’s “memesphere.”

[The man behind Omar Suleiman is featured behind the actress Shadia in an old film (left)

and behind Chuck Norris and dinosaurs (right)]

The most intriguing aspect of these memes is their intention to disrupt mainstream media’s news agendas and offer alternative and often-dissenting critiques with the hope of shifting public opinion. One of the strategies employed that accomplishes this and often exploits a subject matter to a point of saturation is what I will refer to as “subjective omnipresence.” In such instances, not unlike the case of “the man behind Omar Suleiman,” those involved in the creation of memes surrounding a particular topic actively graft the subject of observation into different temporal and spatial contexts so as to suggest the omnipresence of the subject. While to deliver on humor is the first order priority, the secondary objective is to undermine the veneration of public and authority figures. A recent example of this grew out of the first photo of then-Minister of Defense Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s in civilian (rather than military) clothes in which he donned a pair of Ray Ban sunglasses. Despite vowing to never pursue a political career, al-Sisi`s photo that circulated widely in the mainstream media was seen as a move towards introducing him as a presidential figure for the forthcoming elections. Most of the early-doctored images came from members of revolutionary Facebook pages that used their creations to suggestively register their displeasure with the return of the military to public civilian life. Most recently, ahead of the presidential elections this year, a massive online campaign that began as a Twitter hashtag #Vote_for_the_pimp generated thousands of memes ridiculing al-Sisi and placing him in compromising situations and applying “subjective omnipresence” to undermine his reverence and puncture the messianic image he had acquired among his followers.

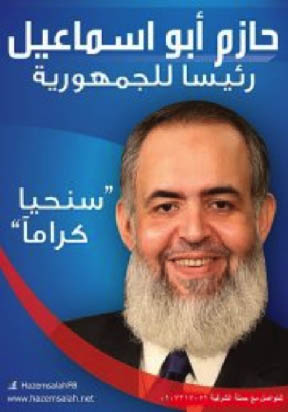

Another example of “subjective omnipresence” preceded the presidential elections of 2012 where Salafi Islamist potential candidate Hazem Salah Abou Ismail came out of virtual anonymity to set the agenda and tone of the election when Egyptians woke up to find his campaign posters plastered on many of Egypt’s roads and buildings. Abou Ismail’s poster campaign was successful at introducing the digital meme community to him and they were quick to respond with their own brand of witty critique by focusing not on his persona or platform but rather on the abundance of his posters. By placing his posters in different contexts—at the Oscars, on the surface of the moon, underneath Barcelona striker Lionel Messi’s shirt, and even being held by the man behind Omar Suleiman—they hoped to not only get laughs but also to undermine his stature as both cleric and politician. However, a few days into the meme frenzy, many on these Facebook platforms began to refrain from producing and promoting these images out of concern that this effort was backfiring and instead giving Abou Ismail even greater visibility.

Locale and Folklore

While many of the early memes circulating online among Egyptians were grafted from American and international online communities (e.g. Yao Ming), with time the confluence of the local and the global became more pronounced in these online forums. This also grew out of the increasing textuality of the memes and a rise in their semiotic complexity. Because of the common exposure to and standardization of Egyptian popular cultural production in mainstream broadcasting—particularly between the 1960s and 1990s before the advent of multichannel regional satellite television—many Egyptians find the same cinematic, musical, and theatrical content recognizable. For this reason, a substantial proportion of memes incorporate references, situations, dialogue, and sensibilities belonging to these now-folkloric collective cultural artifacts. Famous comedy plays such as "Madraset el moshaghebeen" ("The School of the Mischevious"), "Al ‘ayal kebret" ("The Kids Have Grown"),"Shahed mashafsh haga" ("The Witness Who Saw Nothing"), and "El-motazawigun" ("The Married Couples")—often memorized by many Egyptians—are spliced and edited in both stills and video to accentuate messages, level critique, and produce laughter in constructed memes.

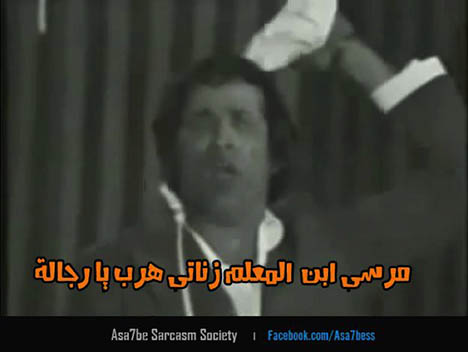

["Oh men, Morsi the son of Mr. Zanaty has escaped" is a modified line from "Madraset el moshaghebeen" referring to the alleged escape of then President Morsi from the Ittihadeya presidential palace as protests gathered in December 2012]

While memes remain vibrant productions that unsettle the status quo and reach millions of Egyptians, they should not be seen as either an alternative or supplement to actual political engagement. Instead they should themselves be seen as acts of political action. With every passing month, attempts to coopt or disenfranchise these meme communities continue—from corporate commodification to state intimidation. Yet, they continue to circumvent the barriers that exist offline to produce some of the most dynamic, innovative, and downright hilarious admonishments of moral and political authority in the country. And while this treatment is a tentative and somewhat cursory highlight into the discursive production in this bustling arena, it is also a call for more substantive analyses that go beyond momentary amusement.

Memes constitute a widening space for the examination and comprehension of cultural history in these turbulent times. A participatory arena for the hybridization of narratives, the marriage of the political and cultural, the amalgamation of the folkloric with the contemporary, and the intersection of the global with the local, memes from Egypt speak to a unique contemporary literacy that evokes, more than any other form of mediated expression, compelling patterns of youth representation and action. Popular memes bring together humor, biting critique, frivolous narcissism, and shameless despondency. Egyptian memes, particularly those that interrogate political power, constitute the Janus-faced conscience of a dissident generation and the disenchanted cynicism of a utopian imaginary.

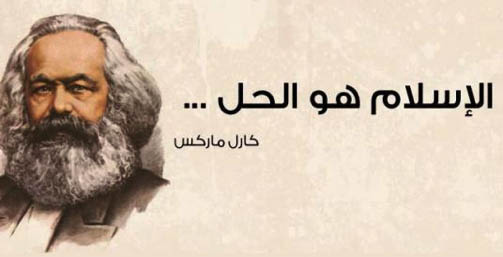

[An aphorism that uses absurdity to undermine the authority and stature of the Muslim Brotherhood by "offensively" matching

their famous slogan "Islam is the solution" with Karl Marx. Photo courtesy of Egypt`s Sarcasm Society]